|

PART IV. CHOOSING ANIMAL HANDLING AND TREATMENT STRATEGIES

A. Primary Considerations

Your animal handling and treatment strategies will clearly

be dictated by the mix of livestock and working animals on

your farm, and your immediate environment (are you on a hill

farm or in a valley? for example). They will also be

heavily influenced by your choice of farming approach (are

you “free range” or “intensively” farming your stock? Do you

use organic “production methods” etc.). In the other Course

Modules in Youth Farm we have given you information which

will enable you to make these choices. Having made them,

you need to determine how to manage the animals on your

farm.

You also need to bear in mind that EU legislation, embodied

in the national laws and regulations of its Member States

requires that farm animals are kept free from disease and

infestations. Failure to do so can lead to prosecution.

But in truth, diseases and infestations significantly affect

the quality and saleability of animal products, and some can

even cause serious illnesses in humans too. So the majority

of farmers need little incentive to keep their animals

healthy.

When animals are being raised for food, it is clear that

there must be restrictions on the chemicals and medicines

used to ensure their well- being and to control their

pests. Within the European Union there is a move towards

the licensing of approved medicines for both human and

animal use. However, it has to be recognised that there are

unlicensed products available and that sometimes farmers can

have their own treatments often based on the principles of

the so called “alternative medicines”. Looking at the wide

range of information available on these factors it is not

possible to make general recommendations. There are a

number of accepted facts concerning the certification of

animal medicines and treatments:

·

The

farmer, the veterinary surgeon, the medicine industry, and

hence the regulatory authorities are faced with many

different patient species, each with its own metabolism and

sensitivities, even to common human treatments. For example

cats are particularly sensitive to aspirin, and paracetamol

is said to be fatal to badgers, even at relatively low

doses. For registered medicines, separate clinical trials

are therefore carried out for every animal species for which

they are used.

·

But

this is complicated further, because farm workers, can

potentially handle large quantities of these medicines,

particularly if incorporating the medicine into feed in a

mill or treating a whole farm flock or herd with preventive

medicines or vaccines So their safety is also considered in

the certification process.

·

Environmental safety is the latest focus, not only for farm

animal treatments. Every product submitted for Market

Authorisation must undergo an "environmental impact

assessment". This is causing some tensions within the

industry because whilst everyone accepts the need for

scrutiny of large volume products used on farms (such as

sheep dips or wormers) the need for an environmental impact

assessment on a cat flea collar (also covered by the

regulations as they are currently written) seems to be

totally counterproductive.

·

"Consumer" protection is also an important factor to be

considered before granting a Market Authorisation,

especially when the animal products are to be eaten. Under

EU law a "maximum residue level" (MRL) must be set for each

"pharmacologically active" substance included in a medicine

for a food-producing animal, also a Withdrawal Period (WP)

must be set for every product and species. It is illegal to

treat a food animal with a medicine that does not have a

defined MRL or WP. But the EU law focuses on the target

species, not the treated individual. This creates a

conflict because animals bred for sport or as pets such as:

racehorses, rabbits or Vietnamese pot bellied pigs must all

be treated with medicines having an MRL even though they

will not be eaten.

From the above we can agree that, in many ways, animal

medicines are even more heavily regulated than human

medicines. And sadly, it has been an inevitable, if

unintended, consequence of this heavy and costly regulation

that the number and range of authorised products has been

eroded whilst the avoidance and evasion of regulations

appears to have increased.

But it is permissible for a vet to use unlicensed medicines

for the treatment of animals (even those being raised for

food), especially if the farmer and vet are responding to

outbreaks of new or unrecognized conditions. This is known

as the

"Cascade". Some see it as a crucial safety valve, others as

a dangerous loophole in the regulations. Whilst the EU

legislation (and that of its Member States), requires that

“no person is allowed to administer any medicine to an

animal unless the product has been granted a Marketing

Authorisation”, there remains a moral, ethical and legal

imperative on animal owners, and a professional duty on

veterinary surgeons, to look after the "animals under their

care". And as with human patients, the lack of an

authorised product does not remove the need for treatment.

The

EU authorities accept that animal owners and vets have to do

their duty. A decision tree, popularly known as the

"Cascade" exists in the legislation and allows the

veterinary surgeon to proceed through a series of decisions

which steadily move away from the ideal,

providing that no

authorised product is available for the treatment of that

specific patient, the vet may prescribe:

1.

A product authorised for that condition in

another species or a product authorised for another

condition but in the same species (off-label use)

2.

If no such product exists, an appropriate

authorised human medicine

3.

If no such product exists, a product prepared

extemporaneously by an authorised person in accordance with

a veterinary prescription.

For

animals grown for food, the requirement for the active

ingredient to have a known MRL remains paramount.

The

directives include many medicines given orally, by

injection, or applied externally such as ointments. Also

falling under these regulations are many pest treatments and

“dips”, such as organophosphates.

These general pesticides can be very hazardous to use.

Section 3 of the course notes provides important information

on the use of sprays and pesticides. Section 4.9 provides

some guidance on the use of dips, and giving treatments in

feed and by injection.

The

diseases and infestations that you need to protect against

will be determined by your immediate environment. Advice is

available from vets and from your local officials of your

Government Ministry responsible for agriculture. A useful

overview produced in the UK can be found

HERE.

A similar useful overview document produced by the Irish

Government can be found at: http://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2003/vetbooklet.htm.

B.

General Safety Policies on Dairy Farms

Dairy farmers often work in isolation, facing risks from

animal behaviour, mechanical hazards, climatic conditions,

and rushed work deadlines.

Spot the hazard

Look for hazard related to lighting, electricity, slips and

trips, training and supervision of new and young workers,

animal behaviour, machinery guarding, heavy lifting and

carrying.

Assess the risk

Check each identified hazard for likelihood and severity of

injury or harm. The greater the risk and severity, the more

urgent it is to minimise or eliminate the risk. Consider

appropriate changes and make sure new hazards are not

created.

Make the changes

The following are to help minimise risks in dairy farming.

-

Have adequate lighting for early morning and evening

milking.

-

Concrete surfaces should be roughened to provide extra

traction for both handlers and stock.

-

Design the milking shed to minimise physical effort.

-

Keep guarding in place on moving parts, e.g. belts and

rotaries.

-

Check guarding on compressors, pumps, electric motors and

grain augers.

-

Have an emergency stop lanyard - in addition to the

forward-stop-reverse lanyard.

-

Have a residual current device (RCD) installed on the

electrical circuit board.

-

Fit all-weather covers on power boards in wet areas.

-

Ensure milk line supports and union joints meet

recommended safety levels.

-

Cover head-high projections like handles on milk filter

casings with padding.

-

Keep exhaust pipes clear of walkways.

-

Maintain exhaust systems in good order to reduce noise and

fumes.

-

Fence off effluent disposal ponds to keep out children and

stock.

-

Clearly mark all water outlets not suitable for human

consumption.

-

Ensure hot water taps are inaccessible to children.

Strain injuries

Activities that can lead to back strain injuries include:

-

long hours working on tractors;

-

stock feeding;

-

fencing;

-

hay and silage preparation;

-

irrigation.

To reduce the risk of back strain injuries,

-

use mechanical aids, such as hoists, trolleys, barrows and

pulleys;

-

use team lifting, planning each task in advance;

-

keep loads small;

-

keep walkways clear;

-

modify work areas to minimise bending, lifting, pulling,

pushing, restraining, lowering and carrying.

-

do repetitive tasks at a comfortable height, with the

least amount of bending, stretching or leaning.

-

develop safe lifting techniques - using the legs and not

the back.

Hot water

-

Ensure hot water is safely guarded.

-

Have safe procedures for working with or near hot water.

-

Make sure hot water taps can be clearly identified.

-

If appropriate, fix clear warning signs next to hot water

hazards.

Remember

-

Ensure adequate lighting for milking.

-

Use specialised equipment where you can.

-

Plan tasks and modify equipment to minimise hazardous

manual handling.

Injuries from cattle relate to a number of factors -

inadequate yard design, lack of training of handlers, unsafe

work practices, and the weight, sex, stress factor and

temperament of animals.

Spot the hazard

-

Check accident records to identify tasks most likely to

cause injury.

-

Consider situations that cause stress and injury to

handlers and stock.

-

Take into account sex, weight and temperament of stock.

-

Consider effects of weather and herding on animal

behaviour, and time allowed for settling down.

-

Check potential hazards and safety advantages of stock

facilities, including mechanical aids and work layout.

-

Consider what training is required before a person can

confidently and competently handle stock.

Assess the risk

-

Using accident records, check which tasks and work

situations are most frequently linked with injuries.

-

Discuss safety concerns of handlers in regard to various

tasks.

-

Check each identified hazard for likelihood and severity

of injury.

-

Assess proposed safeguards and safe procedures for other

hazards.

Make the changes

Here are some suggestions for improving safety in cattle

handling.

-

Always plan ahead. Prepare and communicate safe work

practices. Get assistance if necessary.

-

Wear appropriate clothing, including protective footwear

and a hat for sun protection.

-

Make use of facilities and aids - headrails, branding

cradles, whips, drafting canes, dogs etc.

-

Know the limitations of yourself and others - work within

those limitations.

-

Respect cattle - they have the strength and speed to cause

injury.

Facilities and conditions

-

Yards and sheds should be strong enough and of a size to

match the cattle being handled.

-

Good yard design assists the flow of stock. Avoid sharp,

blind corners, and ensure gates are well positioned.

-

Keep facilities in good repair and free from protruding

rails, bolts, wire etc.

-

Where cattle need restraining, use crushes, headrails,

cradles, etc.

-

Footholds and well-placed access ways are important.

-

Try to maintain yards in non-slippery condition.

-

Cattle are more unpredictable during cold, windy weather.

The stock

-

Hazards

vary according to the age, sex, breed, weight, horn

status, temperament and training of animals. Hazards

vary according to the age, sex, breed, weight, horn

status, temperament and training of animals.

-

Approach cattle quietly, and make sure they are aware of

your presence.

-

Bulls are more aggressive during mating season and

extremely dangerous when fighting. Separate into different

yards where appropriate.

-

Cows and heifers are most likely to charge when they have

a young calf at foot.

-

Heifers can also be dangerous at weaning time.

-

Isolated cattle often become stressed and are more likely

to charge when approached.

-

Cattle with sharp horns are dangerous - dehorning is

recommended where practicable. Dehorned and polled cattle

can still cause injury.

Cattle yarding

-

Avoid working in overstocked yards where you risk being

crushed or trampled.

-

While drafting cattle through a gate, work from one side

to avoid being knocked down by an animal trying to go

through.

-

Take care when working with cattle in a crush, e.g. to

vaccinate, apply tail tags, etc. A sudden movement by

stock could crush your arms against rails or posts.

-

When closing a gate behind cattle in a crush or small

yard, stand to one side, or with one foot on the gate in

case the mob forces the gate back suddenly.

Kicking and butting

-

To avoid kick injuries, attempt to work either outside the

animal's kicking range or directly against the animal,

where the effect of being kicked will be minimised.

-

In dairies there is a high risk of being kicked. Try to

follow a regular routine so as not to alarm cows - e.g. by

placing cold water on their teats.

-

When working on an animal's head, use head bail to

restrain it from sudden movement forwards or back.

-

Take care when using hazardous equipment, such as brands

or knives for castrating or bangtailing.

Stud cattle

-

When working with stud cattle, train animals to accept

intensive handling through gradual familiarisation, e.g.

grooming, washing, clipping.

-

When leading cattle on a halter, never wrap the lead rope

round your arm or hand. If the animal gets out of control,

you could be dragged.

-

Bulls should be fitted with a nose ring. When being led,

their heads should be held up by the nose lead.

Hygiene

-

Be aware of the risks of contracting such diseases as

Leptospirosis or Q Fever when working with animals. These

diseases are transmitted through contact with blood,

saliva and urine. (See section 4.8 for more information.)

-

Hygiene is important. Consider vaccinating herds against

such diseases.

D.

General Safety Criteria for the Handling of

Sheep

Manual handling injuries - wear and tear to the back,

shoulders, neck, torso, arms and legs - are the main

problems to avoid when handling sheep. Awkward postures,

working off balance, and strenuous, repetitive and sudden

stress movements can cause immediate or gradual strain

injuries and conditions.

Spot the hazard

-

Take note of sheep handling activities that put strain on

any part of the body.

-

Unfit, untrained or out of condition workers are most

likely to be injured.

-

Check sheep yarding, handling and shearing facilities for

injury hazards.

-

Check injury records for tasks and situations causing most

injuries.

-

Discuss hazard concerns with other sheep handlers.

Assess the risk

Assess each identified hazard for the likelihood of injury

or harm. Assess also the likely severity of injuries or

harm. The more likely and serious the potential injury, the

more urgent it is to minimise the risks.

Make the changes

The following suggestions are to help farmers and sheep

handlers make sheep handling safer:

-

Use a yard design that will encourage sheep to work

freely.

-

Build yards on sloping ground for better drainage.

-

Keep shadows to a minimum where not required to provide

shade. Build protective coverings over working and

drafting races where practical.

-

Avoid slippery surfaces, especially in races and forcing

yards.

-

Keep dust levels at a minimum.

Fitness and health

People working with sheep should:

-

Exercise regularly, and eat a well balanced diet to keep

fit and maintain required energy levels.

-

Read labels on chemical containers carefully, and follow

manufacturers' instructions and safety directions.

-

Observe recommended withholding periods for drugs or

chemicals before stock are slaughtered.

Working with lambs

-

When marking and mulesing lambs, use a cradle where

feasible. Keeping a firm grip on lambs helps to avoid cuts

and chemical spillage.

-

Catchers should wear protective gloves.

-

Use a work system on cradles that minimises hazards of

being cut, sprayed with chemicals or jabbed with a needle.

-

Sterilise knives, shears and ear pliers, and ensure

operators observe hygiene practices.

Jetting, dipping, drenching

-

Choose chemicals that are most efficient and least harmful

to humans. Always wear protective clothing, goggles and

breathing equipment where specified.

-

Use positive air supply hoods. If headaches or other

discomforts occur after handling chemicals, seek medical

advice and have appropriate health tests. Avoid using

those chemicals in future.

-

Ensure correct mixing rates are used.

-

Keep equipment well maintained, and check regularly to

avoid chemical leakage.

Mustering

-

Plan the muster. Sheep movement is affected by wind

direction, location of water, etc.

-

Allow plenty of time. Do not rush stock.

-

Use dogs to control the mob. High speed chases on bikes or

horses can cause accidents.

Lifting sheep

-

If sheep need to be lifted, get assistance where possible.

-

When lifting alone, sit the sheep on its rump, squat

yourself down, take a firm hold of its back legs while

keeping the sheep's head up to restrict movement. Pull the

animal firmly against your body, and lift using your legs,

not your back.

-

If lifting over a fence, do not attempt to drag the sheep

over. Rather, work from the same side as the sheep.

-

To save lifting, put a drafting gate at the end of the

handling race. It is advisable to have several positions

for "drop gates" in the race to hold sheep that are to be

drafted off.

Rams

-

Rams can be aggressive and unpredictable. Treat them with

caution.

-

When working rams in a race, ensure you are protected from

those behind you. This applies particularly when checking

testicles, etc. A well-positioned drop gate is useful to

reduce the hazard.

Transmittable diseases

-

Animals carry diseases that are transferable to humans. Be

familiar with the symptoms so you can determine if disease

exists in the flock.

-

If signs of disease appear, have the disease confirmed and

animals tested.

-

If the disease is present, treat affected animals

appropriately and vaccinate to prevent further occurrence.

-

Diseases are transmitted by urine, blood and saliva, and

through open wounds (e.g. scabby mouth).

-

Keep open wounds covered. Wash well with water, soap and

antiseptic if contact is made with urine, blood or saliva

from diseased animals.

-

Personal hygiene is important at all times.

E.

General Safety Criteria for the Shearing of

Shee

Hazards in shearing generally involve machinery, electrical

fittings, sheep yard design, slippery and obstructed floors,

sharp tools, equipment and protrusions, chemicals, heat

stress, and strain injuries from repetitive, awkward and

strenuous work.

Spot

the hazard Spot

the hazard

Conduct a safety audit of shearing sheds, pens, flooring,

machinery, wool presses, electrical fittings, connections

and cables, lighting, ventilation, and the experience and

safety training of those involved, particularly young

workers.

Assess the risk

Assess identified hazards for likelihood to cause injury or

harm. Assess also the potential seriousness of the injury or

harm. Consider various safeguards and safe procedures, and

assess these for other possible hazards before deciding a

plan of action.

Make the changes

Many safety innovations have been developed and implemented

to reduce shearing injuries. The following suggestions are

to help farmers minimise risks:

-

Design steps, ramps, pens, entrances, flooring, gates and

latches to minimise the risk of strain and trip injuries

to shearers and helpers.

-

Ensure sheds are well lit and ventilated; cool in summer

and draught free in winter.

-

Keep a suitably equipped first aid box in the shearing

shed.

-

Have suitable, functional fire-fighting equipment

available in shearing sheds and quarters.

Machinery

-

Keep shearing machinery safely guarded to prevent it

catching limbs, clothing or fleeces.

-

Place stopping mechanisms within ready reach in case of

emergency.

-

Ensure a safe distance between shearing positions, to

prevent the risk of downtubes clashing and creating cut

hazards.

-

Keep handpieces well maintained to eliminate vibration

injuries.

-

Choose quiet machinery or isolate noisy machinery to

prevent hearing damage.

-

Choose wool presses designed not to trap workers' hands.

-

Consider having electric motors on wool presses to reduce

noise and air pollution.

-

Consider providing back support harnesses and equipment

for shearers.

Manual handling

-

Keep shearing floors and passage ways clean and clear of

obstructions.

-

Ensure floors in catching pens are kept clean and dry to

reduce slip hazards.

-

Allow sheep to empty out and settle down before moving

them into the shed.

-

Consider providing back support equipment for shearers.

-

Keep shed hands clear of shearers unless they need to be

there, or are called on for assistance.

-

Keep dogs out of the working area, and don't tie them up

where people can trip over them.

Fitness and health

-

Shearers and rural workers should exercise regularly and

eat a well balanced diet to guard against injury and

maintain the required energy levels.

-

In hot weather, take regular drinks of cool water or

non-alcohol fluids to avoid heat stress.

-

Maintain a good posture during physical work, and use your

legs to lift, not your back.

F.

General

Safety Criteria for Horse Riding General

Safety Criteria for Horse Riding

Horses have the speed, strength and ability to cause injury.

Riders need training and skill, and the concentration and

ability to handle unexpected situations. Clothing and

equipment are important for safe riding and handling of

horses.

Spot the hazard

Look for hazards relating to rider training and experience,

the horse's training and temperament, hazardous terrain and

weather conditions, difficult roundup work, clothing,

footwear and riding equipment.

Assess the risk

Check identified hazards for likelihood and severity of

injury or harm. Consider the background, training and

experience of horses and riders. Where risk of injury or

harm is considered likely, plan safer procedures.

Make the changes

Here are some suggested ways of reducing risk.

-

Plan ahead - consider safe work practices. Get assistance

if necessary.

-

Wear appropriate gear - leather soled riding boots are

recommended as they are designed to slip easily out of the

stirrup in case of an accident. Do not use boots with

half-sole repairs. Jeans, jodhpurs or long trousers will

prevent chafing, and a hat will provide protection from

the sun.

-

An approved riding helmet (polo or pony club style) should

be worn where above average risk is involved, e.g.

inexperienced riders, horse-breaking etc.

-

Know your limitations, and avoid riding horses that are

likely to exploit those limitations.

The equipment

-

Keep bridles and bits in good condition, and fitted so the

horse is comfortable.

-

Ensure saddles and girths are kept in good repair -

stirrup leathers, girth straps and surcingles should be

well oiled and checked regularly.

-

Stirrup irons should be of a size that allows the foot to

slip in and out freely, without allowing it to slip

through.

-

Keep saddle cloths free from burrs and other foreign

material.

-

Horses vary in conformation, temperament, ability and

levels of training. Some require breastplates or cruppers

to keep the saddle in place, and running rings, nosebands

or headchecks to keep their head and neck in a position

for easy control.

-

A breastplate is a good safeguard in case the girth breaks

or comes loose.

The horse

-

Great care is needed when galloping close to a beast at

high speed. It is extremely dangerous to allow a horse to

touch a running beast behind the shoulder. The horse can

fall by touching the beast's hind legs, or from the beast

turning completely under the horse's neck.

-

In stock yards, be careful riding under gate caps. Some

are too low for the horse and rider to pass under safely.

-

High speed chases on horses can cause accidents - where

practicable, use dogs to control stock.

-

Extra care should be taken when riding in boggy or

slippery conditions.

-

Riders should be matched to horses that are within their

handling capabilities. Do not assign an inexperienced

person with a flighty, uneducated horse.

-

Mounting is easier if the horse is facing uphill.

-

If there is no yard to ride in, frisky horses should be

taken to a creek bed or sandy area. The horse finds it

harder to buck in sand, and the rider finds it softer to

fall on.

Difficult horses

-

It is not advisable to persevere with horses that are

likely to buck, bolt or become uncontrollable. Some

tolerance however is generally accepted during the

breaking-in and early stages of training.

-

If a horse is likely to buck, it is best to saddle it and

give it some exercise prior to mounting. This can be

carried out in a number of ways, e.g. by "lunging" or

leading it from another horse. The horse should then be

mounted and ridden in a small yard before being ridden in

an unconfined area.

-

If a horse is likely to bolt, it should first be ridden in

a yard. If a horse bolts in an unconfined area, the rider

should remain calm and gradually circle the horse until

the horse comes under control.

-

Riders should remain alert and in a position of control

while mounted - adjusting equipment is a job to be carried

out from the ground.

G.

General Safety Criteria for the Handling of

Pigs

Pig handlers face injuries from the size, strength and

temperament of the animals they tend. Injuries may also

relate to training of handlers, the safe design of pens,

lanes and other yarding, and the administering of drugs and

chemicals. Noise in pig sheds can reach levels that require

hearing protection.

Spot the hazard

Check the safety of pens, floors and lanes, handling and

restraining of animals, safety training for new and young

workers, safe lifting methods, safe use of chemicals, and

protection from diseases carried by pigs. Study worker

injury records for evidence of hazardous jobs and

situations.

Assess the risk

Assess whether any of the hazards identified are likely to

cause injury or harm, and base safety decisions on the

likelihood and possible severity of the injury or harm.

Make the changes

The following suggestions are to help minimise or eliminate

the risk of injury or harm in pig handling:

-

Check pens and lanes are large and strong enough for the

pigs being handled.

-

Ensure pen design assists the smooth flow of pigs - avoid

sharp, blind corners, and ensure gates are well

positioned.

-

Keep facilities in good repair and free from protruding

rails, bolts, wire and rubbish.

-

Where pigs need restraining, use crushes and nose ropes.

-

Try to maintain non-slippery conditions, especially in

lanes and loading yards.

Stock factors

-

Safety in pig handling varies according to a number of

factors - age, sex, breed, weight, temperament and

training of the animal.

-

Boars can be aggressive and unpredictable. Treat them with

caution.

-

Boars are most aggressive during mating, and extremely

dangerous when fighting.

-

Prevent boars from coming in contact with each other at

all times.

-

When moving boars, use a drafting board.

Lifting pigs

-

When lifting pigs, get assistance where possible.

-

When lifting alone, sit the pig on its hindquarters, squat

down, take a firm hold of the back legs, pull the animal

firmly against your body and lift, using your legs and not

your back.

-

Remember, when lifting a pig this way, make sure the pig's

head is positioned so that it cannot bring its head back

into your face.

Chemicals, vaccinations and injections

-

Read labels on chemicals and antibiotic containers

carefully - follow manufacturers' instructions and safety

directions.

-

Sterilise needles, teeth cutters and ear pliers, and

ensure operators observe hygienic practices.

-

Observe recommended withholding periods for drugs and

chemicals before pigs are slaughtered.

-

Wear appropriate protective clothing.

-

If headaches or any other discomfort is suffered after

handling chemicals, seek medical advice and have

appropriate tests.

-

Avoid these chemicals if possible in future, and use full

protective clothing and breathing filters when handling

chemicals in the feed mill.

-

Ensure correct dosage rates are maintained.

Transmittable diseases

-

Animals carry diseases that can be transmitted to humans.

Be familiar with the symptoms so you can tell if these

diseases exist in the herd.

-

If signs of disease appear, have the disease confirmed and

animals tested. If the disease is present, treat affected

animals appropriately and vaccinate to prevent further

occurrence. Maintain a vaccination program.

-

Diseases like Leptospirosis are transferred by urine,

blood and saliva, and through open wounds. Keep open

wounds covered and wash well with water, soap and

antiseptic if contact is made with blood, urine or saliva

from diseased animals (See Topic 19 on Zoonoses for

further information).

-

Maintain personal hygiene at all times.

H.

General Safety Criteria to Minimise the Risks

of Zoonoses

"Zoonoses" is the name given to animal diseases that can

cause illness in people. Often animal carriers are not

obviously ill, yet people in contact with them can become

infected. Farm animals are a common source of infection,

and people most at risk are abattoir workers, farmers,

veterinarians, livestock handlers and animal laboratory

workers. Leptospirosis, Q Fever, Hydatid Disease and Orf

are the zoonoses of most concern in Western Australia.

Spot the hazard

-

Review infection control during animal handling

procedures.

-

Be aware of contamination sources.

-

Check availability and use of suitable disinfectants.

-

Check handling and disposal procedures for contaminated

materials.

-

Check if farm dogs eat meat or offal from farm-killed

sheep or wild animals.

Assess the risk

Consider the likelihood of disease or harm occurring. Assess

whether existing safe procedures are working or need

improving. Establish whether others on the farm have

immunity to various zoonoses, either through vaccination or

having had the disease.

Make the changes

The following information is to help farmers understand

zoonoses hazards, so that the risk of infection can be

minimised or eliminated.

Leptospirosis

Flu-like symptoms include headaches, muscle pains, fever,

chills, sensitivity to light and a stiff neck. Some people

also develop kidney or liver problems.

-

Avoid direct contact with animal urine, contaminated

water, and birth fluids, especially from pigs.

-

Infection enters through cuts in the skin or through the

linings of eyes, nose or throat.

-

Leptospirosis can be treated with antibiotics. If you

think you may be infected see a doctor quickly.

-

Clean benches and floors with detergents or disinfectants.

Eradicate rats and mice. Ensure good drainage of stock

areas, and hygienic disposal of effluent.

Q Fever

Q Fever also feels like 'flu', with headaches, muscle pains

and fever, that may progress to pneumonia. Some people

develop liver and heart problems.

-

Avoid breathing contaminated dust, air infected by animal

after-birth and birth fluids, drinking unpasteurised milk,

or contact with contaminated straw, wool, hair or hides.

-

Found in a wide range of domestic and wild animals, such

as sheep, goats, bandicoots and wallabies.

-

Disinfect, burn or bury infected materials.

-

Treat and cover cuts quickly.

-

Milk should be pasteurised or boiled.

-

Q Fever in humans can be treated with antibiotics. If you

think you are infected see a doctor quickly.

Hydatid Disease

In the early stages of Hydatid Disease no symptoms may be

felt. Symptoms depend on the site of the parasitic cyst

which is the cause of the disease. The most common site is

in the liver.

-

Symptoms due to a large liver cyst may be a sense of

weight, vomiting, feeling overly full after meals, or

pain, indigestion and jaundice (abnormal yellow

discolouration of the body).

-

Cysts may also occur in the lungs. Early symptoms may be

coughing, chest pain or coughing blood. The first symptom

may be coughing up salty fluid after rupture of a cyst.

This may lead to shock from allergy, itching of the skin

or chest infection.

-

Cysts in other body organs may cause seizures, blindness,

deafness, kidney pain or heart problems. All these forms

are potentially deadly, and the rupture of a cyst at any

site can cause death from shock due to allergy.

-

Hydatid disease is caught by humans from dogs that have

eaten the raw meat or offal of sheep, cattle, goats,

kangaroos or wild pigs carrying Hydatid cysts.

-

Eating with infected hands or other hand-to-mouth contact

after patting a dog is enough for eggs of the Hydatid worm

to be swallowed and cause infection.

-

When swallowed, Hydatid eggs are transported by the blood

to other parts of the body.

-

Dogs and dingoes carry the worm in their gut without

becoming ill.

Treating Hydatid Disease

Hydatid cysts can cause serious illness in humans. The only

effective treatment is surgery to remove the cysts,

sometimes in conjunction with anti-worm drugs. Some cysts in

vital organs cannot be surgically removed.

Reducing infection risk

-

Don't allow dogs to eat raw meat or offal from farm killed

sheep, goats or cattle, or feral and native animals like

pigs, goats and kangaroos.

-

Make sure dogs are given a regular tape worm treatment -

consult your vet for the most effective program.

-

Dogs should be prevented from eating animals that die on

the farm or in the bush. Carcasses should be disposed of

as quickly as possible.

-

Don't allow children to play with stray dogs.

Orf (scabby mouth)

The disease known as Orf or scabby mouth in sheep and goats

can affect humans in other ways.

-

Red areas or pimple-like lesions appear, often at the site

of a graze or cut. This becomes a blister surrounded by

red swollen skin that can turn into an ulcer and take four

to six weeks to heal. Regional lymph glands may become

swollen in some cases.

-

Contact with sheep or sheep products is the usual cause of

infection to humans, though goats are occasionally a

source of infection.

-

The Orf virus usually enters through cuts or abrasions.

-

Orf sores should be treated with antiseptic dressings to

prevent bacterial infection and spread. Usually healing

and recovery occurs even without treatment, and you will

not get the disease again.

Health Alert card

An Occupational Health Alert card is available from your

local authorities/government agencies responsible for

supervising farming activities (usually the Ministry of

Agriculture, or a Department for Occupational Health and

Safety) to alert doctors that a patient may have caught a

disease from animals. An example is provided in the

Glossary to these notes.

Reducing infection risk

Cuts and abrasions from handling sheep should be treated

with disinfectant and covered to avoid reinfection.

Learn to recognise the disease in animals (thick scabs or

ulcers on the nose, lips, eyes or other hairless areas) and

avoid contact.

I.

Safe Use and Handling of Animal Medications &

Parasite Controls

Dipping

This is a process normally applied to sheep and mostly

carried out in the UK due to local legislation.

Sheep dips are classed as "veterinary medicines" rather than

as “pesticides” and at one time were used by every sheep

farmer in the UK to protect sheep against external

parasites. The majority of formulations contain

organophosphate active ingredients, which it is now known

can lead to both short-term and long-term effects on users.

Some argue that UK farmers have not been properly protected

either by the law or by regulators.

Sheep suffer from external parasites such as blowflies, or

from keds, ticks, lice, and scab. In the

UK the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (now

known as DEFRA) published advice for sheep farmers stating

"Sheep scab is a disease caused by a parasitic mite which

lives on the skin surface. The feeding activities of the

mite cause irritation and distress. This can result in

stunting or severe loss of condition, loss of fleece, and

death - especially of lambs ..." Dipping, by running sheep

through a bath of dip solution, aims to rid animals of such

parasites.

In

the UK in 1988, about 40 million sheep on 18,765 farms were

dipped. The manufacturers' association, the National Office

of Animal Health (NOAH) refer to "Britain's 95,000 sheep

farmers and their staff dipping sheep twice a year [in the

1980s]." Until 1989, the law in the UK required compulsory

dipping twice a year in an effort to eradicate scab, a

notifiable disease. In 1989 and 1990, only one dip was

required. In 1992, dipping for scab ceased to be

compulsory, and the disease became no longer notifiable.

What are the costs and benefits and risks of the use of

particular pesticides? A prominent commentator on dipping,

Dr Jack Done of the Centre for Agricultural Strategy,

Reading University, considers that compulsory dipping has

brought us no nearer eradication than when it was begun in

1973. Eradication was successful in the period 1952 to

1972. Since 1973, statistical analysis shows that the mean

annual incidence of scab in the five double-dipping years

(1984-88) was not significantly different from that in any

other five consecutive years. or from the whole period since

sheep scab was introduced in 1972 . For 95 cases of scab in

1990, 35 million sheep had to be dipped.

The

human cost of sheep dipping, the adverse health effects

resulting from the exposure of operators and others to

organophosphate active ingredients in the dips, is only now

being recognised.

Farmers are concerned that they have little protection from

hazardous chemicals. Protective clothing alone is not a

practical method of preventing exposure to dipping solution

for a farmer having to haul a heavy sheep in and out of

dips, and the "aerosol effect" of sheep shaking themselves

dry after dipping means that the atmosphere is soon laden

with chemical.

So

far it is uncertain whether the route of exposure for those

who have suffered adverse effects is dermal, inhalatory, or

by ingestion. In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive has

said that tests done in the 1980s showed that there were no

traces of OP vapour in breathing areas, but considered that

solvents and phenols might be inhaled and cause adverse

effects. Phenol dips are to be withdrawn (see under

Regulatory control). Current HSE advice does not recommend

a face mask when dipping.

The

Veterinary Medicines Directorate in the UK has taken a

different view. It has published advice for farmers which

is headlined "Sheep dip concentrates contain either an

organophosphorous or a pyrethroid insecticide. Some may

also contain phenols. These substances can be absorbed

quite readily in the body through the skin, nose and mouth.

Careless handling can endanger human health."

Given these facts farmers are quite justified in asking for

clear guidance on whether face masks required. The Ministry

advice is not clear, "Dip concentrates and dip wash must be

handled with care at all times - some constituents if

inhaled or absorbed through the skin can cause poisoning".

Protective clothing is advised by the literature for

performing dipping operations. Current advice from HSE

recommends personal protective equipment, which should

include "rubber gloves, coverall, and a faceshield when

handling the concentrate and rubber boots, rubber gloves and

waterproof coat or bib apron when handling the diluted

liquid and freshly dipped sheep".

Although protective clothing is recommended. there are as

yet no agreed standards for protective clothing for

pesticides throughout the EU. For example, in Germany, the

Government has introduced new testing and "instructions for

use" requirements for protective clothing. The pesticide

manufacturer must include all details on wearing protective

clothing in his "instructions for use" literature. In the

UK there is no clearly defined system of approval of

protective clothing materials.

The effects of dips on the environment:

In the UK, one angry farmer wrote to the magazine,“Farmers'

Weekly” to complain "After spending an entire day some years

ago telephoning the Government Ministry Departments, Safety

Management organizations, the water boards, the National

Farmers’ Union, to ask for advice on safe disposal, we had

numerous instructions about how not to dispose of it, but

not one practical piece of advice as to what we should

actually do to get rid of it."

Recent advice to farmers on disposing of sheep dip is to

pour it down "soakaways" or to spread it on fields away from

surface waters. The EC considers that this may breach the

1980 Groundwater Directive, and that the dip must be

incinerated, or dumped at licensed landfill sites.

A

report by the Tweed River Purification Board has shown that

sheep dipping caused pesticide contamination in 17 out of 20

river catchments in the Borders area of southern Scotland in

autumn 1989; 40% of sheep dips were thought likely to cause

pollution. The pesticides concerned were diazinon and

propetamphos. The Water Research Centre expressed concern

about the lack of ecotoxicological data for such products.

The

results of an earlier survey of the Grampian area, published

at the same time, also reported pollution by organochlorine

and organophosphate dips . Indeed, an estimate was made of

the "polluting potential" of the usage, disposal and

spillage of chemical from a typical sheep dip tank. The

resulting concentration of, say, propetamphos would lead to

a flow of between 10 and 20 times the EC drinking water

limit over a 24-hour period.

River authorities are concerned at the lack of invertebrate

life that characterises rivers polluted by OP dips. Other

'non-target' species at risk, are waterfowl and geese which

are more sensitive to OPs than other farm animals.

Giving Treatments in Feed

The most common form of food additive are Macrolides, a

group of antibiotics used for the treatment of animals, but

outside of the EU they are also used for growth promotion.

For these as any other medicinal additive to feed it is

essential to wear appropriate personal protective equipment

(as specified in the MSDS supplied with the product) when

mixing your feed. It should be noted that the digestive

system of ruminants means that antibiotics and other

anti-microbial drugs are generally best given by injection

since there is a poor absorption of these drugs through the

digestive system.

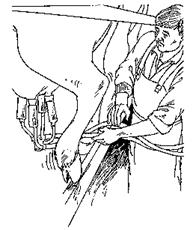

Giving Treatments by injection

The most common injection given on a farm will generally be

for the vaccination of stock against a range of illnesses.

When giving injections it is important that you are safe

from kicking, biting, scratching, or pecking, but also that

you avoid breaking the needle in the animal. This may not

be straight forward as you can never predict how the animal

will react. The best guidance and advice on vaccinations

can be obtained from your local vet who will be familiar

with the diseases and conditions that you will need to

vaccinate against and can show you how to administer the

injection.

Some guidance has also been prepared by organisations

representing specific farming communities. For example the

Canadian Government’s Ministry of Agriculture and Food has

provided guidance on the vaccination of pigs and how to

avoid needles breaking inside the pigs. These can be found

here, but are summarised here, since the guidance will

apply to almost any situation:

Prevent needles from breaking

- use proper injection techniques

-

Never straighten bent needles for reuse. This is the

single most common cause of breaking needles during

injections.

-

Never inject pigs on the move. Restrain them prior to and

during injection with your hands, a sorting board or a

snare, according to the size of the animals to be

injected.

-

Change needles frequently. Replace needles after injecting

either 10 pigs, or one litter of piglets.

-

Use the correct length and gauge of needle according to

the weight of the pigs. Inject pigs at right angles to the

skin (see CQAÒ Injection Techniques For Swine poster).

-

Always inspect needles for damage following each

injection.

-

Use a plastic syringe whenever practical. Needles with

plastic syringes will usually break off at the plastic

hubs, leaving visible and grippable stubs which are easy

to remove from pigs. Aluminum or stainless steel needles

are stronger than plastic ones and may not offer this

advantage when they break.

Adopt good management practices

-

Use trained and designated personnel to inject the pigs.

-

Inject pigs in the neck. Never inject pigs in the ham, due

to carcass quality concerns.

-

Manage needles on the farm through inventory checking and

record keeping–what goes in, must come out.

-

Establish a farm protocol for handling any incidence of

broken needles. Educate staff on proper identification and

reporting of broken needles. Make this mandatory.

Adopt new technologies and products

-

Detectable Needles - Use needles that can be detected by

high-speed metal detectors in packing plants. These

needles are now manufactured in Canada and the United

States and test results show they are more easily detected

than standard needles. Maple Leaf Pork and Olymel already

announced that effective June 30th

producers who ship hogs to their plants must use

detectable needles on the farm. Other packers may follow

suit soon.

Note that detectable needles can't replace proper injection

technique and good management practice. Detectable needles

that break must still be reported prior to shipping.

Furthermore, packing plant metal detectors are not entirely

fool proof in finding foreign materials, because some cuts

of meat are not easily checked by the equipment and false

positives or negatives are possible.

·

Needle-free injectors - The most recent development for

injections is the availability of needle-free injectors.

These injectors can be used for all sizes of pigs and are

best suited for injecting large numbers of animals at one

time, such as for vaccination. In addition to the

elimination of broken needles, these products claim other

benefits:

o

no cross- contamination of disease causing biological agents

such as PRRS virus

o

improved carcass quality

o

increased human safety

o

no requirement for disposal of used needles

Protocols for handling broken needles

Needles can break during injections. When a needle breaks,

take the following steps to ensure the incident is handled

appropriately.

Step

1.

Mark the animal immediately

·

Identify the hog with a permanent mark.

·

Record the incident, including the location of the broken

needle and the ear tag number.

Step

2.

Remove the broken needles

·

Attempt to remove the broken needle immediately if possible.

·

Call your veterinarian for assistance if the needle cannot

be removed.

·

Make sure all the pieces of a broken needle are recovered.

Note that the cost of removing the needle at this stage may

be much lower than allowing the needle to remain, where it

may get lost and possibly destroy the value of the whole

carcass. In addition, allowing broken needles to remain

could compromise the animal's well-being.

Step

3.

Slaughter the animal on-farm

·

If removal of the broken needle has failed, consider the

option of slaughtering the animal on-farm.

Step

4.

Inform your marketing agency and/or your packer

If steps 1, 2, and 3 are not possible, then take the

following action:

·

Ear tag the animal.

·

Contact the Ontario Pork Producers Marketing Board and/or

your packer at least one week prior to shipping an animal

with a broken needle, or a suspected broken needle, from the

farm. Be aware that different packers may have different

requirements for identification and for notification. Note

that informing the marketing board or a packer means a phone

call to a person; not just a message left on an answering

machine, a fax or an email. Shipping and/or receiving an

animal that may contain a broken needle is a major event.

Everyone involved should be notified at least seven days in

advance. Prior notice allows for proper arrangements to be

made for the hog.

Equivalent guidance for cattle is given at

http://www.dairyinfo.gc.ca/cdicofqm10.htm, including

advice on how to prevent bruising during the vaccination. |